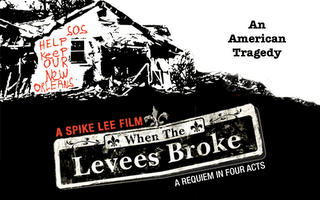

Spike’s Haunting 'Requiem'

by Esther Iverem--SeeingBlack.com Editor and Film Critic

“When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts” is a powerful elegy for the dead of Hurricane Katrina, for the death of New Orleans and for naivety about how the U.S. government treats its poor. Directed by Spike Lee, it is a requiem in the hands of a meditative son, on par with Mozart’s “Requiem” or Earth, Wind and Fire’s “Open Our Eyes.”

The documentary, which premieres on HBO, Monday, August 22 at 8p.m., is a tour de force of humanity, horror and living history. The first two acts recount the days immediately before, during and after Hurricane Katrina stuck the U.S. Gulf Coast on August 29, 2005. While much of New Orleans was spared the brunt of the storm which, instead, decimated coastal communities in Mississippi, ensuing heavy rains breached the city’s poorly constructed levee system and 80 percent of the city was submerged beneath a toxic stew of floodwater, raw sewage and residue from the region’s petrochemical industries.

News organizations broadcasted images around the world of desperate city residents stranded on rooftops, highways and at two emergency shelters at the city’s Superdome and convention center. Though the shelters were set up to provide respite, they became islands of misery, as tens of thousands waited, and some died, without water, food or other relief from the federal government. A police and military response to looters, and to news reports of outrageous crimes later proven to be untrue, depicted victims of this tragedy as an undeserving and dangerous criminal class.

What Lee adds to this familiar recent history is our story—close-up, first-hand accounts from those who lived to tell. “It was deplorable at that [Super] dome,” says Audrey Mason, who evacuated her flooded home after hearing loud explosions come from the direction of the levee in her Gentilly neighborhood. She is one of many longtime Black New Orleans residents who believe that a section of the levee in their neighborhood was deliberately destroyed, in order to prevent flooding in wealthier, White areas. “I not only heard the explosion, I felt the explosion,” she says.

While Lee does not dwell long on such suspicions, he uses interviews with historians and vintage film footage to illustrate how they are rooted in history. For example, after a storm in 1927, a White Louisiana community was deliberately flooded and during Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Black residents believe but do not have proof that their neighborhoods were also deliberately flooded.

Portions of Act I and Act II are a tragicomedy of elected leadership and “official speak.” Lee reminds us, however, that the incompetence with which the federal government built levees and handled the crisis had consequences that were deadly rather than funny. He ends the second act with a finale for the dead that we rarely see in the coverage of our domestic tragedies (or from our military invasions abroad either)—a montage of variously grotesque corpses that are bloated, mangled or floating in flood waters.

Lee’s talent for choosing characters for this horrible story sometimes seems to mimic what he has done in his career making feature films. Just as Audrey Mason of could be like the sage and no-nonsense characters played by Ruby Dee, Phyllis Montana-LeBlanc, a tart-tongued resident of New Orleans East, could be the equivalent of a sassy Rosie Perez [parents be forewarned: cursing is definitely allowed in this requiem]. Terrence Blanchard, also a native of New Orleans, provides the jazz riff here that runs through so many 40 Acres and Mule productions.

Similarly, for the combined Acts III and IV, which will be shown Tuesday night at 8 p.m. [All four parts will air August 29th on the anniversary of the disaster], Lee begins with a sweeping historical prelude that rivals his work on “School Daze,” his feature film that explored life at a historically Black college. While there would seem to be little left unsaid after the first half, Lee uses these two acts to follow the scattering of some of the tens of thousands of primarily Black New Orleans residents to new places around the country. Many have found a better life and vow not to return what they feel is the scene of a crime. “If they wanted us in New Orleans, they wouldn’t have tried to drown us and kill us,” says Mason. “So I’m not going to go back so they can try to finish the job.”

Lee also chronicles the desire of some to return to the city and rebuild their lives, though their houses have been completely destroyed or rendered uninhabitable. Graphic images make clear that, one year after Katrina, much of New Orleans still looks worse than war zones in Iraq, Afghanistan or Beirut. “It’s like someone dropped a nuclear bomb on every part of the city,” says Calvin Mackie, a professor at Tulane University.

In the aftermath, there is also ongoing horror: bodies still being found in locked homes that were supposedly checked by search teams; children burying parents and parents burying children; insurance companies refusing to pay claims, even to those with flood insurance; a new tide of violence and crime from the city’s dispossessed youth; a city emptied of much of its Black population; a city looking at both nature’s fury and government in bewilderment.

They knew that this could happen,” says Benny Pete, a musician from the Lower 9th Ward of government officials. “It’s almost like they let it happen.”

“When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts” is a powerful elegy for the dead of Hurricane Katrina, for the death of New Orleans and for naivety about how the U.S. government treats its poor. Directed by Spike Lee, it is a requiem in the hands of a meditative son, on par with Mozart’s “Requiem” or Earth, Wind and Fire’s “Open Our Eyes.”

The documentary, which premieres on HBO, Monday, August 22 at 8p.m., is a tour de force of humanity, horror and living history. The first two acts recount the days immediately before, during and after Hurricane Katrina stuck the U.S. Gulf Coast on August 29, 2005. While much of New Orleans was spared the brunt of the storm which, instead, decimated coastal communities in Mississippi, ensuing heavy rains breached the city’s poorly constructed levee system and 80 percent of the city was submerged beneath a toxic stew of floodwater, raw sewage and residue from the region’s petrochemical industries.

News organizations broadcasted images around the world of desperate city residents stranded on rooftops, highways and at two emergency shelters at the city’s Superdome and convention center. Though the shelters were set up to provide respite, they became islands of misery, as tens of thousands waited, and some died, without water, food or other relief from the federal government. A police and military response to looters, and to news reports of outrageous crimes later proven to be untrue, depicted victims of this tragedy as an undeserving and dangerous criminal class.

What Lee adds to this familiar recent history is our story—close-up, first-hand accounts from those who lived to tell. “It was deplorable at that [Super] dome,” says Audrey Mason, who evacuated her flooded home after hearing loud explosions come from the direction of the levee in her Gentilly neighborhood. She is one of many longtime Black New Orleans residents who believe that a section of the levee in their neighborhood was deliberately destroyed, in order to prevent flooding in wealthier, White areas. “I not only heard the explosion, I felt the explosion,” she says.

While Lee does not dwell long on such suspicions, he uses interviews with historians and vintage film footage to illustrate how they are rooted in history. For example, after a storm in 1927, a White Louisiana community was deliberately flooded and during Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Black residents believe but do not have proof that their neighborhoods were also deliberately flooded.

Portions of Act I and Act II are a tragicomedy of elected leadership and “official speak.” Lee reminds us, however, that the incompetence with which the federal government built levees and handled the crisis had consequences that were deadly rather than funny. He ends the second act with a finale for the dead that we rarely see in the coverage of our domestic tragedies (or from our military invasions abroad either)—a montage of variously grotesque corpses that are bloated, mangled or floating in flood waters.

Lee’s talent for choosing characters for this horrible story sometimes seems to mimic what he has done in his career making feature films. Just as Audrey Mason of could be like the sage and no-nonsense characters played by Ruby Dee, Phyllis Montana-LeBlanc, a tart-tongued resident of New Orleans East, could be the equivalent of a sassy Rosie Perez [parents be forewarned: cursing is definitely allowed in this requiem]. Terrence Blanchard, also a native of New Orleans, provides the jazz riff here that runs through so many 40 Acres and Mule productions.

Similarly, for the combined Acts III and IV, which will be shown Tuesday night at 8 p.m. [All four parts will air August 29th on the anniversary of the disaster], Lee begins with a sweeping historical prelude that rivals his work on “School Daze,” his feature film that explored life at a historically Black college. While there would seem to be little left unsaid after the first half, Lee uses these two acts to follow the scattering of some of the tens of thousands of primarily Black New Orleans residents to new places around the country. Many have found a better life and vow not to return what they feel is the scene of a crime. “If they wanted us in New Orleans, they wouldn’t have tried to drown us and kill us,” says Mason. “So I’m not going to go back so they can try to finish the job.”

Lee also chronicles the desire of some to return to the city and rebuild their lives, though their houses have been completely destroyed or rendered uninhabitable. Graphic images make clear that, one year after Katrina, much of New Orleans still looks worse than war zones in Iraq, Afghanistan or Beirut. “It’s like someone dropped a nuclear bomb on every part of the city,” says Calvin Mackie, a professor at Tulane University.

In the aftermath, there is also ongoing horror: bodies still being found in locked homes that were supposedly checked by search teams; children burying parents and parents burying children; insurance companies refusing to pay claims, even to those with flood insurance; a new tide of violence and crime from the city’s dispossessed youth; a city emptied of much of its Black population; a city looking at both nature’s fury and government in bewilderment.

They knew that this could happen,” says Benny Pete, a musician from the Lower 9th Ward of government officials. “It’s almost like they let it happen.”